Monetary Rules Report

January 27, 2026

Summary

Federal Funds Rate Target Range: 3.50 - 3.75%

Expected Target Range after Jan. 28 FOMC: 3.50 - 3.75%

Rule-Implied Range: 3.86 - 5.83%

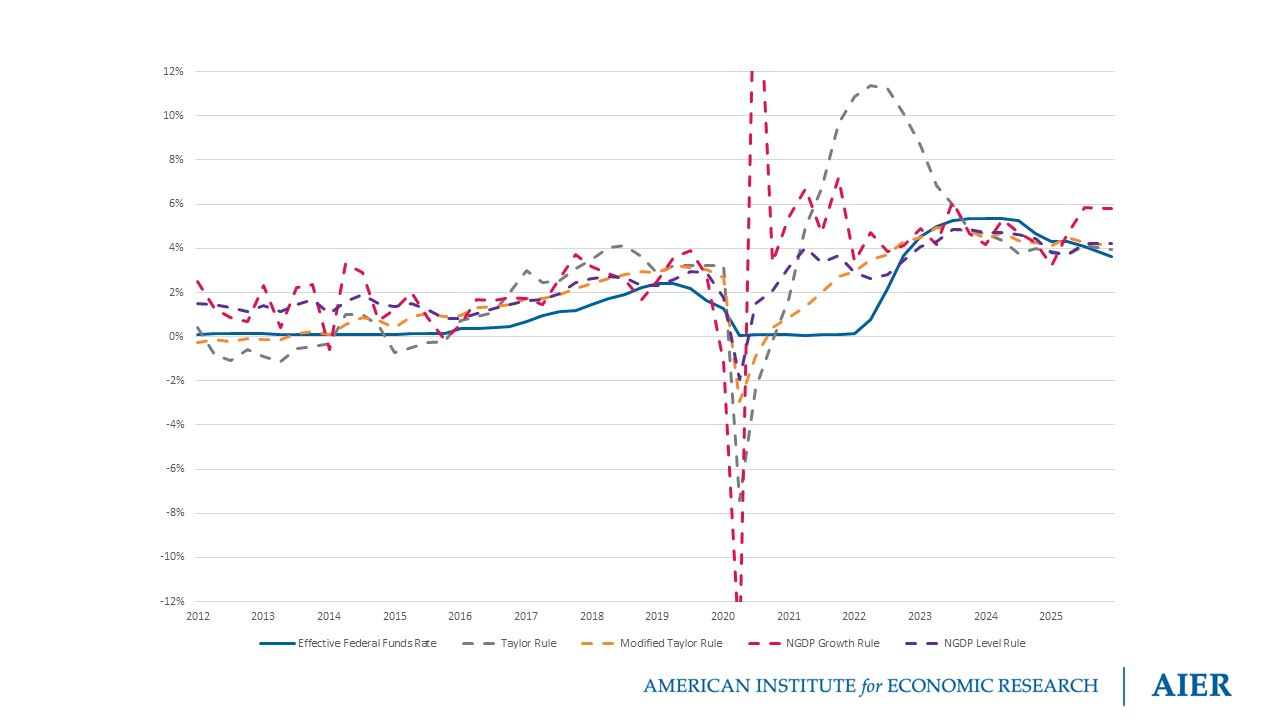

The Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) is expected to keep its federal funds rate target in the range of 3.50 - 3.75% at this week’s meeting. This target is slightly below the range prescribed by monetary rules. The original Taylor rule prescribes a target of 3.94% and a modified Taylor rule prescribes a target of 4.00%. Due to strong third quarter growth in spending, a nominal gross domestic product (NGDP) level rule (4.24%) and NGDP growth rule (5.83%) prescribe somewhat higher policy rates, as noted parenthetically.

Chair Powell has described recent FOMC decisions as “risk-management” cuts aimed at guarding against a weakening labor market. The leading monetary policy rules suggest that additional insurance is unnecessary at this stage. While an immediate reversal is unlikely, the rules point toward holding steady — and potentially reconsidering one of last year’s cuts — rather than moving toward further easing.

Background

A monetary policy rule is a systematic guideline central banks can use to determine the appropriate stance of monetary policy. The most popular example, called the Taylor rule, instructs the central bank to set its federal funds rate target based on the prevailing rate of inflation and real economic activity. A nominal gross domestic product (NGDP) targeting rule, in contrast, suggests that the central bank should aim to stabilize nominal spending.

Taylor Rules

In his original formulation, Stanford economist John Taylor proposed that the federal funds rate target be set equal to a long-run neutral rate and adjusted as inflation deviates from the central bank’s target or real economic activity deviates from the economy’s full-employment potential. When inflation is above target or real economic activity exceeds potential, the central bank should raise its target rate. When inflation is below target or real economic activity falls short of potential, the central bank should lower its target rate. More formally, the original Taylor rule is written as follows:

where ft is the federal funds rate target, rt* is the real long-run neutral interest rate, πt* is the central bank’s inflation target, πt is the prevailing rate of inflation, and γt is a measure of the deviation in real economic activity from potential (.e.g., the unemployment gap).

Following Taylor’s original formulation, economists have proposed many other Taylor-type rules. For example, some make the rule “forward-looking” by including forecasts of expected future inflation rather than the most recently available historical data. The forward-looking Taylor rule is justified on the grounds that monetary policy often needs to act preemptively in anticipation of future developments, particularly with regard to stabilizing inflation expectations.

Another approach is to smooth the rule by including the weighted value of the most recent federal funds rate on the right-hand side of the formula. The smoothed Taylor rule is justified on the grounds that excessive interest rate volatility increases uncertainty and potentially destabilizes the link between short-term and long-term interest rates.

The modified Taylor rule presented above is both smoothed and forward-looking.

NGDP Rules

Some economists have developed Taylor-type rules that will stabilize nominal spending—or, nominal gross domestic product (NGDP). These rules advise the central bank to raise its policy rate when nominal spending growth is too high and lower its policy rate when nominal spending growth is too low. More formally, an NGDP targeting rule is written as follows:

where ft is the federal funds rate target, ρ is a smoothing parameter between 0 and 1, (rt* + πt*) is the nominal neutral interest rate, Ω is an adjustment parameter, and Nt is the nominal spending gap.

The nominal spending gap can take various forms. One option is to use the difference between the most recent NGDP growth rate and a 4% target growth rate, which is consistent with the idea that real GDP growth is typically around 2% and the Federal Reserve targets 2% inflation. Another option is to use the nominal spending gap, which measures the difference between actual nominal spending and expected nominal spending. The first option targets a growth rate for nominal spending, which does not account for previous deviations from target. The second option targets the level of nominal spending, which advises the central bank to make up for recent mistakes.

Estimates

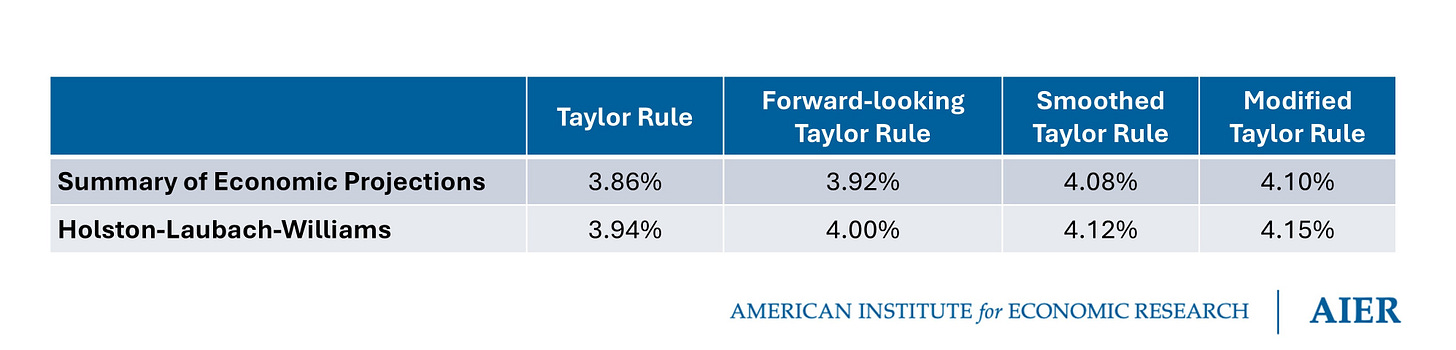

Estimates for the original, smoothed, forward-looking, and modified (i.e., smoothed and forward-looking) Taylor rules are presented in Table 1. Two estimates are constructed for each rule. The first estimate uses the median projected longer run federal funds rate in the most recent Summary of Economic Projections as a proxy for the nominal neutral rate of interest, rt* + πt*. The second estimate uses the New York Fed’s Holston-Laubach-Williams estimate for the real interest rate, rt*.

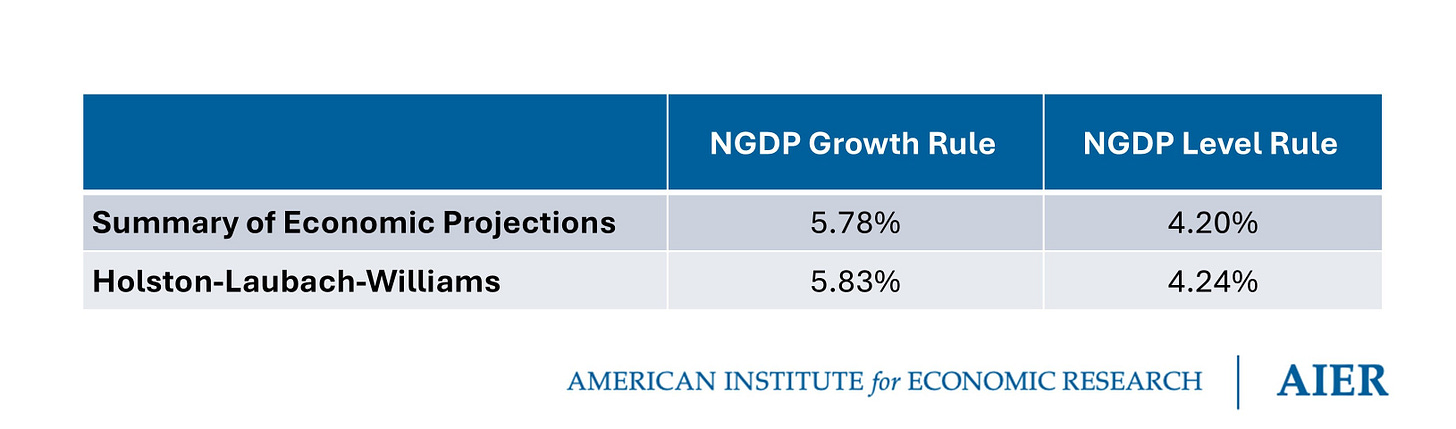

Estimates for the NGDP growth and level rules are presented in Table 2. As with the Taylor rules presented above, I construct two estimates for each rule using the Summary of Economic Projections and New York Fed’s Holston-Laubach-Williams estimate. I employ a smoothing parameter equal to 0.5 and an adjustment parameter equal to 1.0 for all four estimates

.

References

Beckworth, D., & Hendrickson, J. R. (2020). Nominal GDP targeting and the Taylor rule on an even playing field. Journal of Money, Credit and Banking, 52(1), 269-286.

Beckworth, D., & Horan, P. J. (2024). A two-for-one deal: Targeting nominal GDP to create a supply-shock robust inflation target. Journal of Policy Modeling, 46(6), 1071-1089.

Beckworth, D., & Horan, P. J. (2025). The fate of FAIT: salvaging the Fed’s framework. Southern Economic Journal, 91(4), 1391-1403.

Hendrickson, J. R. (2012). An overhaul of Federal Reserve doctrine: nominal income and the Great Moderation. Journal of Macroeconomics, 34(2), 304-317.

Luther, W. J. (2024). Neutral Nominal Spending and the Nominal Spending Gap. Sound Money Project Working Paper.

Taylor, J. B. (1993). Discretion versus policy rules in practice. In Carnegie-Rochester conference series on public policy (Vol. 39, pp. 195-214). North-Holland.